Covidence covers the basics of scoping review

As the medical literature continues to grow, the people who rely on it to make good decisions face a challenge: to summarise it accurately and effectively. Scoping reviews are one approach among many to synthesise our knowledge and produce something useful, accessible, and reliable. Here we take a closer look at scoping reviews, why we need them, and how to start writing one ✍️.

Scoping reviews ask broad questions like “What is already known about this intervention?” or “What outcomes have already been examined in the treatment of this condition?” They search for evidence and describe what they find. If this type of question has already triggered alarm bells as you contemplate sifting through everything that is known on a particular intervention, don’t worry. With some careful thought and preparation you and your team can plan a scoping review that is both manageable for the reviewers and useful for the reader. Ready? Let’s go! 🚀

What is a scoping review?

Scoping reviews are considered by many to be a type of systematic review, but the aims and methods differ in important ways.

Systematic reviews ask a targeted question about the effectiveness or the safety of an intervention. They assess the certainty of the evidence and aim to produce a single point estimate. Their results are sometimes used to inform policy. Scoping reviews, on the other hand, don’t usually contain a critical appraisal of the evidence. They often describe, rather than synthesise, the information they find. Their results might inform further research but they are not used to shape policy.

Despite these important differences (you can read more about them here) the two review types have a lot in common. Scoping reviews are systematic. Their methods are transparent and they should be replicable. As with systematic reviews, it is good practice to state the methods up front in a protocol or research plan, to justify any deviations from the plan, and to use two people to make screening decisions and extract data.

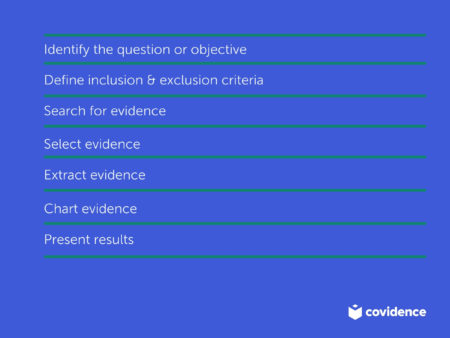

The data extraction phase in a scoping review is known as ‘charting’. This is the process of collecting relevant information from the included sources using a structured form 📋. Depending on the review question, the charting might involve characterising study data rather than extracting outcomes.

The basic process for conducting a scoping review is shown in figure 1.

Why do we need scoping reviews?

- To inform a systematic review. The results of a scoping review can guide the choice of question and the inclusion criteria in the systematic review. This can prevent ’empty’ systematic reviews, i.e. reviews that find no eligible studies.

- For their own sake. Scoping reviews can produce a summary of what is known, map the literature and put it in the context of a particular time period, population, discipline or field.

Scoping reviews are useful in new areas of research. One recent example is the Cochrane rapid scoping review Care bundles for improving outcomes in patients with COVID‐19 or related conditions in intensive care.

Getting started

There are a lot of things to consider when undertaking a scoping review. Here we cover a few tips to get started. For more advice and expert guidance, see the scoping review chapter in the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Manual for Evidence Synthesis 📘.

Preparation

As with any research project, the key to success is in the planning. Consult widely with colleagues to pinpoint the question and the inclusion criteria. Think about the end users. Who are they? What do they need? Why are you summarising this evidence? A scoping review is a big project. A broad review question is fine but reviewers must be clear about the purpose and specific about the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Defining these clearly now will save a lot of time and prevent problems further down the line 🎯.

Scoping reviews refer to included sources rather than included studies because they also consider editorials, book chapters, expert opinion, and policy documents. A librarian or information specialist will be able to give expert advice on how to formulate a question that enables your team to identify the relevant source material and how to write a search strategy that will retrieve a manageable volume of results for screening 📚.

It is also a good idea to talk to people who have already done scoping reviews and to read up on the methodology and the reporting requirements, starting with the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews.

Framework

The JBI recommends the PCC framework (Population, Concept, Context) for formulating scoping review questions. Using this framework, the title of the Cochrane rapid scoping review described above can be expressed as the following question:

What evidence is available on…

⚕️ care bundles [Concept] to improve outcomes for

🤒 patients with COVID-19 or related conditions [Population] in

🏥 intensive care [Context]?

PCC gets reviewers thinking about the What, the Who, and the Where for the topic of interest. It guides reviewers to a broad question while applying sensible parameters. If an initial search identifies many thousands of records, reviewers should be prepared to narrow the scope of the review by revisiting the review question and the eligibility criteria.

Searches often uncover information that reviewers were previously unaware of, such as keywords or search terms. It is often necessary to refine the review question, the eligibility criteria, and the search strategy in light of this new information. In this way, the search stage becomes an iterative process that can be adjusted as necessary to achieve the objectives of the review. Clear and rigorous reporting of these iterations and the reasons for them is very important to ensure transparency.

Think ahead

When embarking on a scoping review, it’s important to think ahead to how you will chart the data and present the results 🤔. Aim to be specific and to develop a structured form to keep the process as clear as possible. Choices for the presentation of results should be informed by the objectives of the review.

If you plan to narrow the scope of your review due to time or budget constraints, be clear about the reasons for doing so and the effect that this will have on the review. Prepare to acknowledge the limitations of your work as part of the discussion of your results.

The process of screening sources in a scoping review is similar to the process used in a systematic review. Scoping reviews typically report the decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of sources using a flow diagram. The scoping review’s charting form works on the same principles as the data extraction form used in systematic reviews.

Many scoping reviews do not critically appraise the sources of evidence, but if you do plan to include this in your review, a clear rationale and a description of the methods should be given.

Conclusion

A scoping review is a worthwhile project that gathers together all the available evidence on a particular topic. Getting started on a scoping review requires careful planning of the whole process, from formulating the question to presenting the results.

The screening and data collection processes of scoping reviews have much in common with those of systematic reviews. Whether you’re planning a systematic review, a scoping review, or both, Covidence can speed up screening and data collection to keep your project on track and on time. Sign up for a free trial today!