PICO framework for systematic reviews

PICO is an essential tool for systematic reviewers who are studying the effects of interventions. It’s a simple framework for formulating a research question and deciding on the eligibility of studies for inclusion in the review. It considers four basic elements:

👩👩👦👦 The Population (or patients)

💊 The Intervention

💊 The Control

📏 The Outcome

Structuring a review question in this way brings useful focus and helps review teams to make a detailed plan of the work ahead. Think of PICO as a methodological golden thread that runs all the way through your review and holds everything together conceptually.

So how does that work in practice? Let’s walk through the systematic review process step by step to take a look at PICO in action.

1. The review question ❓

The PICO framework is the basis for most review questions, for example:

🌓 “In children with nocturnal enuresis (population), how effective are alarms (intervention) versus drug treatments (comparison) for the prevention of bedwetting (outcome)?”

Sometimes the review question misses out the comparison, for example if the review compares the intervention with no treatment or with usual care:

👟 “How effective is physical therapy (intervention) for reducing foot pain (outcome) in runners with plantar fasciitis (population)?”

🤧 “How effective is echinacea (intervention) in preventing common cold (outcome) in healthy adults (population)?”

2. The search strategy 🔍

PICO then informs the search strategy by providing relevant search terms that will be used to retrieve studies. Although it is good practice to use PICO to inform the search, it is not usually advisable to use the ‘Outcomes’ element of PICO in a search strategy. This is because it can reduce the recall of the search, which risks excluding potentially relevant studies (for example, those that measured the outcome of interest but did not report it in the published paper).

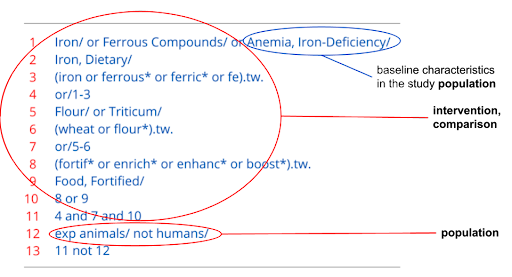

Let’s take a look at the search strategy used for the Cochrane review ‘Wheat flour fortification with iron and other micronutrients for reducing anaemia and improving iron status in populations‘ in Figure 1.

The search term “Iron/ or Ferrous Compounds” in line 1 aims to identify studies containing the intervention of interest (fortified wheat flour). Lines 2 to 11 develop this to make the search for studies with a relevant intervention as comprehensive as possible. In this review, the same search terms are used for both the intervention and the comparison (non-fortified wheat flour).

Line 12 relates to the population. This review doesn’t specify particular characteristics of the population in the review title. A review with a narrower scope might, for example, look at pregnant women, or patients with celiac disease. In this example, the reviewers are conducting a broad search and just want to make sure that the studies they retrieve pertain to humans.

The second portion of line 1, “Anemia, Iron-Deficiency/” could relate to the outcomes of interest (iron levels in the study participants will be measured to assess the effectiveness of the intervention). However, anemia and iron deficiency are more likely to be included here as baseline characteristics in the study population (i.e. some of the individuals that are randomized to the treatment or the control arm at the start of the trials will have anemia). That’s because specifying outcomes in the search strategy might exclude relevant data, as we saw in section 2.

3. Screening the studies 👀

Once the search is complete, the PICO-informed inclusion and exclusion criteria support the efficient screening of studies. Conveniently, studies imported into Covidence can be screened alongside a list of inclusion and exclusion criteria at both the title and abstract and the full text review stages.

4. Data extraction 📥

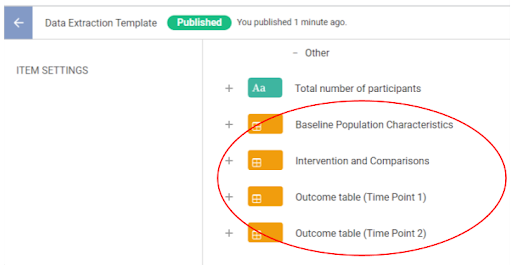

PICO isn’t just used to determine the eligibility of studies for a review. It can also be used to group the study data for analysis. Covidence’s data extraction template uses the PICO elements to organise relevant information about the characteristics of the included studies (Figure 2). It’s easy to use and fully customizable. Sorting study data in this way prepares reviewers for the analysis and synthesis that comes next.

If your review doesn’t follow the PICO format, you can still use Covidence to collect and extract data from included studies. ‘Population’ is just the label applied to the unit that is randomly assigned to the intervention or the comparison. If that unit is not an individual patient but, for example, a school, an eye, or a side of the mouth (hello, dentists! 👋), the data extraction form can still be used to sort the study data according to your needs.

5. Data synthesis 📈

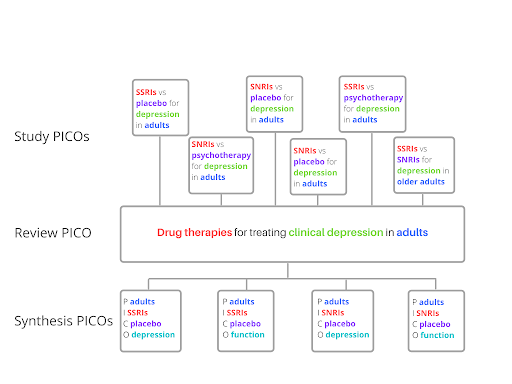

To re-cap, we’ve seen so far that PICO is used to set the inclusion criteria and to organise study data ahead of synthesis. Cochrane makes a useful distinction between these two uses. The first is called the review PICO because it’s what is used in setting the review question. The second is the PICO for each synthesis. This specifies how data will be grouped, or perhaps split, into a number of separate syntheses. These two concepts are distinct from a third, the PICO of the included studies. This is the PICO defined by the individual studies whose data are included in the review.

How would this look in practice? Well, for illustrative purposes (no real trials or real systematic reviews here), the three PICOs could look like those shown in Figure 3. The review PICO produces a relatively broad question. To answer it, reviewers must examine data from eligible studies, each of which has its own PICO (the PICO of the included studies). The review team then uses a PICO for each synthesis to make decisions on how to analyse and present the gathered data.

Deciding on exactly how to organise the data for analysis in a review will depend on factors including the type and amount of data. If you have reason to expect that the treatment effect could differ according to a characteristic of the population such as age or sex, you could plan a subgroup analysis. But to avoid the pitfalls of data dredging and to minimise the risk of bias, subgroup analyses should be specified and justified when writing the protocol or project plan.

Conclusion

Planning is an essential part of conducting a successful systematic review. PICO helps reviewers to plan each stage of a review, from the initial question, through searching and selecting studies, right up to the data collection and synthesis. Taking the time to understand PICO and how it can be used to best effect is a good way to prepare for the work ahead and to ensure your analysis stays focused on, and relevant to, the review question.

1. Frandsen, T. F., Nielsen, M. F. B., Lindhardt, C. L., & Eriksen, M. B. (2020). Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 127, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.07.005

2. Field MS, Mithra P, Peña-Rosas JP. Wheat flour fortification with iron and other micronutrients for reducing anaemia and improving iron status in populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD011302. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011302.pub3.

3. McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE, Thomson HJ, Johnston RV, Thomas J. Chapter 3: Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.