Covidence covers five key steps to formulate your review question using PICO

You’ve decided to go ahead. You have identified a gap in the evidence and you know that conducting a systematic review, with its explicit methods and replicable search, is the best way to fill it – great choice 🙌.

The review will produce useful information to enable informed decision-making and to improve patient care. Your review team’s first job is to capture exactly what you need to know in a well-formulated review question.

At this stage there is a lot to plan. You might be recruiting people to your review team, thinking about the time-frame for completion and considering what software to use. It’s tempting to get straight on to the search for studies 🏃.

Take it slowly: it’s vital to get the review question right. A clear and precise question will ensure that you gather the appropriate data to answer your question. Time invested up-front to consider every aspect of the question will pay off once the review is underway. The review question will shape all the subsequent stages in the review, particularly setting the criteria for including and excluding studies, the search strategy, and the way you choose to present the results. So it’s worth taking the time to get this right!

Let’s take a look at five key steps in formulating the question for a standard systematic review of interventions. It’s a process that requires careful thought from a range of stakeholders and meticulous planning. But what if, once you have started the review, you find that you need to tweak the question anyway? Don’t worry, we’ll cover that too ✅.

📌 Consider the audience of the review

Who will use this review? What do they want to know? How do they measure effectiveness? Good review teams partner with the people who will use the evidence and make sure that their research plan (or protocol) asks a question that is relevant and important for patients.

📌 Think about what you already know

How much do you need to know about the topic area at this stage? Ideally, enough to come up with a relevant, useful question but not so much that your knowledge influences the way in which you phrase it. Why? Because setting a review question when you are already familiar with the data can introduce bias by allowing you to direct the question in favour of achieving a particular result. In practice, the review team is very likely to have some knowledge of relevant studies and some preconceived ideas about how the treatments work. That’s fine – and it’s useful – but it’s also good practice to recognise the influence this knowledge and these ideas might have on the choice of question. Issues of bias will come up again as we work through the rest of these steps.

If not enough is known about the subject area to ask a useful question, you might undertake a scoping review. This is a separate exercise from a systematic review and is sometimes used by researchers to map the literature and highlight gaps in the evidence before they start work on a systematic review.

📌 Use a framework

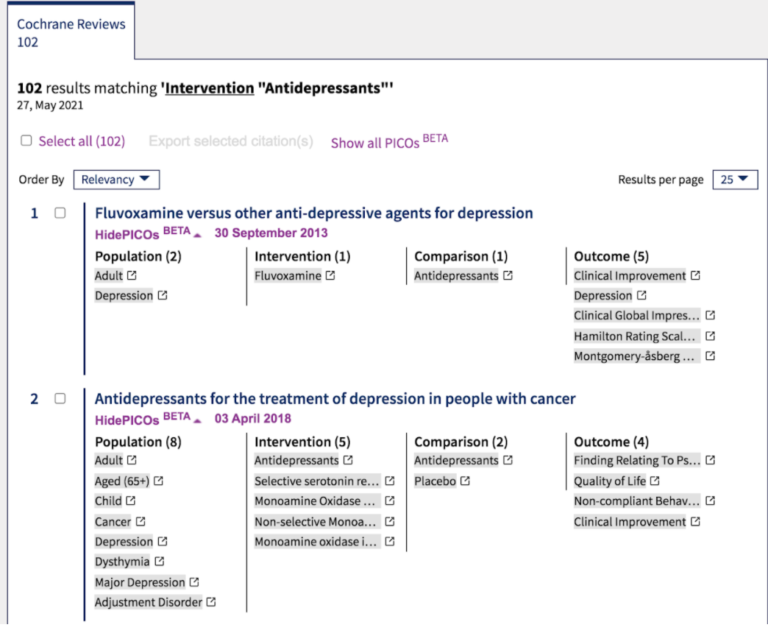

Faced with a heady mixture of concepts, ideas, aims and outcomes, researchers in every field have come up with question frameworks (and some great backronyms) to help them. Question frameworks impose order on a complex thought process by breaking down a question into its component parts. A commonly used framework in clinical medicine is PICO:

👦 Population (or patients) refers to the characteristics of the people that you want to study. For example, the review might look at children with nocturnal enuresis.

💊 Intervention is the treatment you are investigating. For example, the review might look at the effectiveness of enuresis alarms.

💊 Comparison, if you decide to use one, is the treatment you want to compare the intervention with. For example, the review might look at the effectiveness of enuresis alarms versus the effectiveness of drug therapy.

📏Outcomes are the measures used to assess the effectiveness of the treatment. It’s particularly important to select outcomes that matter to the end users of the review. In this example, a useful outcome might be bedwetting. (Helpfully, some clinical areas use standardised sets of outcomes in their clinical trials to facilitate the comparison of data between studies 👏.)

But back to bedwetting. In our example, a PICO review question would look something like this:

“In children with nocturnal enuresis (population), how effective are alarms (intervention) versus drug treatments (comparison) for the prevention of bedwetting (outcome)?”

PICO is suitable for reviews of interventions. If you plan to review prognostic or qualitative data, or diagnostic test accuracy, PICO is unlikely to be a suitable framework for your question. In Covidence you can save your PICO for easy reference throughout the screening, extraction and quality assessment phases of your review.

📌 Set the scope

The scope of a review question requires careful thought. To answer the example PICO question above, the review would compare one treatment (alarms) with another (drug therapy). A broader question might consider all the available treatments for nocturnal enuresis in children. The broad scope of this question would still allow the review team to drill down and separate the data into groups of specific treatments later in the review process. And to minimise bias, the intended grouping of data would be pre-specified and justified in the protocol or research plan.

Broader systematic reviews are great because they summarise all the evidence on a given topic in one place. A potential disadvantage is that they can produce a large volume of data that is difficult to manage.

If the size of the review has started to escalate beyond your comfort zone, you might consider narrowing the scope. This can make the size of the review more manageable, both for the review team and for the reader. But it’s worth examining the motivations for narrowing the scope more closely. Suppose we wanted to define a smaller population in the example PICO question. Is there a good reason (other than to reduce the review team’s workload) to restrict the population to boys with nocturnal enuresis? Or to children under 10 years old? On the basis of what is already known, could the treatment effect be expected to differ by sex or age of the study participants? 🤔 Be prepared to explain your choices and to demonstrate that they are legitimate.

Some reviews with a narrow scope retrieve only a small number of studies. If this happens, there is a risk that the data collected from these studies might not be enough to produce a useful synthesis or to guide decision-making. It can be frustrating for review teams who have spent time defining the question, planning the methods, and conducting an extensive search to find that their question is unanswerable. This is another reason why it is useful for the review team to have prior knowledge of the subject area and some familiarity with the existing evidence. The Cochrane Handbook contains some useful contingencies for dealing with sparse data.

Covidence can help review teams to save time whatever the scope and size of the review. In Covidence, data can be grouped to the review team’s exact specification for seamless export into data analysis software. The intuitive workflow makes collaboration simple so if one reviewer spots a problem, they can alert the rest of the team quickly and easily.

📌 Adjust if necessary

Systematic reviews follow explicit, pre-specified methods. So it’s no surprise to learn that the review question needs to be considered carefully and explained in detail before the review gets underway. But what about the unknown unknowns – those issues that the review teams will have to deal with later in the process but that they cannot foresee at the outset, no matter how much time they spend on due diligence?

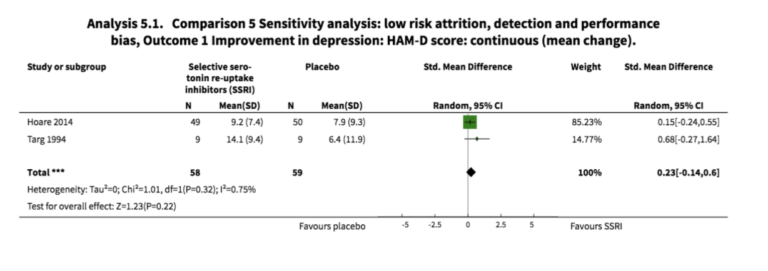

Clearly, reviews need the agility to control for issues that the project plan did not anticipate – strict adherence to the pre-specified process when a good reason to deviate has come to light would carry its own risks for the quality of the review. So if an initial scan of, for example, the search results indicates that it would be sensible to modify the question, this can be done. The research plan might make explicit the process for dealing with these types of changes. It might also contain plans for sensitivity analysis, to examine whether these choices have any effect on the findings of the review. As mentioned above with regard to scope, it might be difficult to defend a data-driven change to the question. And as before, the issue is the risk of bias and the danger of producing a spurious result.

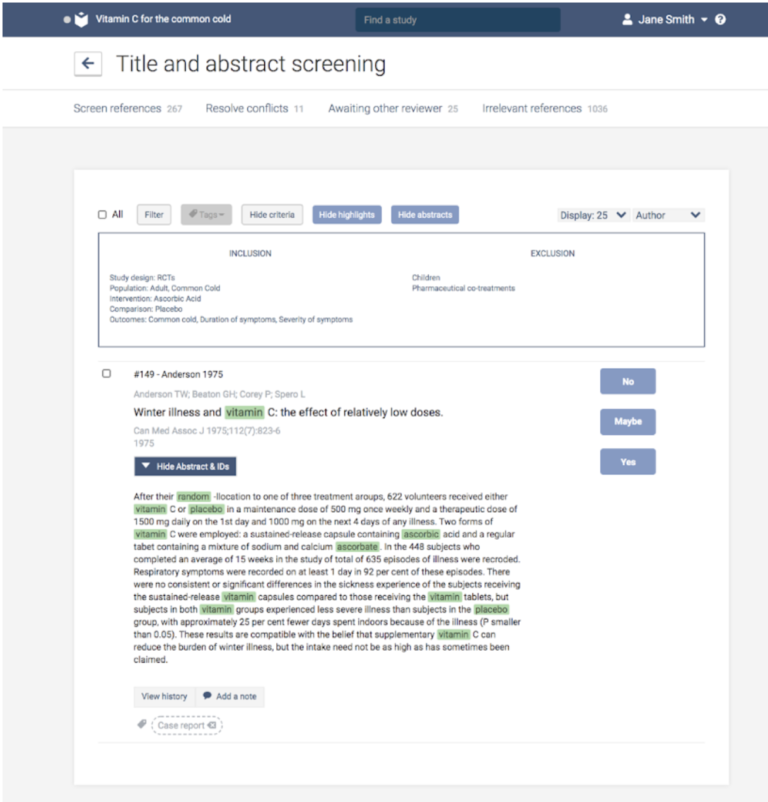

(Figure 4. Image from Eshun‐Wilson I, Siegfried N, Akena DH, Stein DJ, Obuku EA, Joska JA. Antidepressants for depression in adults with HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD008525. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008525.pub3. Accessed 27 May 2021.)

This blog post is part of the Covidence series on how to write a systematic review.

Sign up for a free trial of Covidence today!