Are you ready to get acquainted? Let’s meet the newest members of the systematic review family!

Systematic reviews are generally considered the most reliable source of evidence for decision making because they apply prespecified scientific methods to a synthesis of all the information on a given research question 🙌. Their value in decision making and guideline development is widely recognised by consumers, researchers, patients and clinicians.

A lot has changed since the first systematic reviews were published in the late 1970s. The rate of research output continues to accelerate and new and innovative ways of reviewing the evidence continue to emerge. These share the scientific approach of systematic review while addressing some limitations of the standard model, for example:

- Systematic reviews are costly and take a long time to produce. The need for good evidence is often urgent.

- Systematic reviews answer a specific clinical question. In real life, the useful question is sometimes broader.

- Once published, systematic reviews can quickly become out-of-date as new evidence emerges. When evidence becomes incorrect in this way, it has the potential to cause harm.

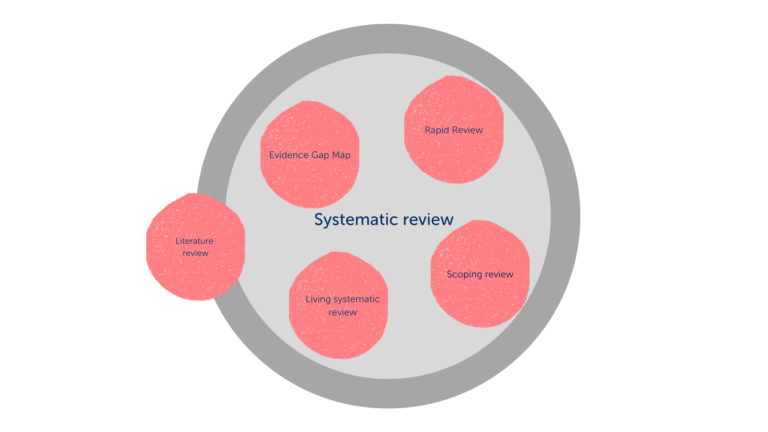

The newer types of review have been likened to biological species that belong to the same family¹. An inexhaustive and unofficial taxonomy could look something like this:

Figure 1: Systematic reviews are ‘rooted in the scientific method’² but not all literature reviews take this approach

Are you ready to get acquainted? Let’s meet the newest members of the systematic review family! 👋

1. Rapid review 🚀

Rapid reviews aim to produce a rigorous synthesis quickly. The process operates within prespecified limits (for example, by restricting searches to articles published during a specific timeframe) and is usually run by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in systematic review methods. Artificial intelligence and machine learning can also be used to speed up the screening process by ordering papers so that those most likely to be relevant appear first. The work of the review team is concentrated into a relatively small amount of focussed time.

Fundamentally, the review process for rapid reviews is the same as for a more traditional systematic review: the emphasis is on a replicable prespecified search, and screening methods that minimise the risk of bias.

✅ Published example: The authors of Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals With Coronavirus: A Rapid Review To Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing used Covidence for evidence synthesis.

2. Scoping review 🧭

Before starting work on a systematic review, some researchers conduct a scoping review to find out more about an existing body of evidence. Scoping reviews are exploratory and they typically address a broad question. For example, ‘What treatments work for Alzheimer’s disease?’ or ‘What do we already know about rates of juvenile reoffending over the last 20 years?’. Researchers conduct scoping reviews to assess the extent of the available evidence, to organise it into groups and to highlight gaps. If a scoping review finds no studies, this might help researchers to decide that a systematic review is likely to be of limited value and that resources could be better directed elsewhere.

Just like systematic reviews, scoping reviews have prespecified eligibility criteria, search the literature, screen the results and select evidence for inclusion. The data extraction stage, in which the review team creates a descriptive summary of the evidence, is known as ‘charting’. The Joanna Briggs Institute provides expert guidance on undertaking a scoping review.

✅ Published example: The authors of The Messages Presented in Electronic Cigarette–Related Social Media Promotions and Discussion: Scoping Review used Covidence to screen their studies.

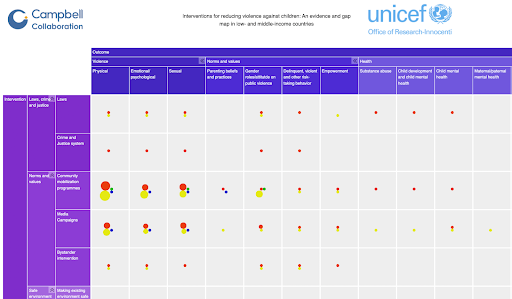

3. Evidence gap map 🗺️

Systematic reviews rely on the presence of studies. Scoping reviews can expose the absence of them. Evidence gap maps take this absence a few stages further by examining not only the evidence, but also the holes in the evidence in order to tell us more about them 🍩. Evidence gap maps can include both systematic reviews and primary studies and they provide a visual overview of the availability of evidence. Why? So that policy makers, guideline developers, and funding bodies can see exactly where future research is needed. And just as importantly, evidence gap maps help to avoid the research waste generated by repeating studies that have already proven conclusive.

Although the evidence gap map looks very different from the other members of the family (it’s a sophisticated infographic), it has a pre-specified protocol, a systematic search strategy, clear inclusion criteria, and systematic reporting, just as we would expect from a systematic review. The Campbell Collaboration provides expert guidance on undertaking evidence gap maps.

✅ Published example: The Campbell Collaboration produced Interventions for reducing violence against children: An evidence and gap map in low- and middle-income countries for Unicef (Figure 2).

4. Living systematic reviews 🔁

Updating a systematic review can become a huge task. Review authors face information overload in the form of a growing number of new studies to screen. They might also lose valuable members of their team to other projects over time. Living systematic reviews turn the task of updating into a flexible and continuous process that is easier to manage than a traditional update. The literature searches are run at regular intervals. Newly identified studies are then screened and the relevant data extracted and synthesised in an iterative process that ensures the evidence is always up-to-date.

Covidence’s review framework has been designed to support the process of living systematic reviews. New studies can be added to the screening or the full-text review stage at any time and extraction can also be updated and repeated as necessary within the same project.

✅ Published example: For a thorough introduction to living systematic reviews, check out this article by Covidence CEO, Dr Julian Elliott.

What about meta-analysis?

You might be wondering where meta-analysis fits into all of this. Often used interchangeably with systematic review, the term meta-analysis refers more correctly to a particular statistical technique that is sometimes used in a systematic review. Meta-analysis takes data from a group of studies and shows their estimated results together with a summary measure on a forest plot. Any of the review types discussed above could include one or more meta-analysis.

It’s all about the methods

Any review can be done systematically. Some literature reviews are conducted along systematic lines with exhaustive, prespecified searching and measures taken to minimise bias. Others are deliberately selective. They explore the literature from the author’s perspective with the aim, perhaps, of demonstrating their knowledge of a particular topic. This sort of literature review is not part of the systematic review family (see Figure 1).

While article titles are a useful guide, it’s a good idea to keep a critical eye on the methods sections of any and all reviews you read. Did the authors actually use systematic methods of conduct and reporting? When it comes to assessing the quality of the studies in your own review project, you decide! 🤔

Conclusion

The systematic review family is growing all the time. Whatever type of review you’re planning to do, Covidence can save you time. Our software is designed by systematic reviewers, for systematic reviewers and we have an extensive knowledge base and a team of experts to answer all your questions along the way.